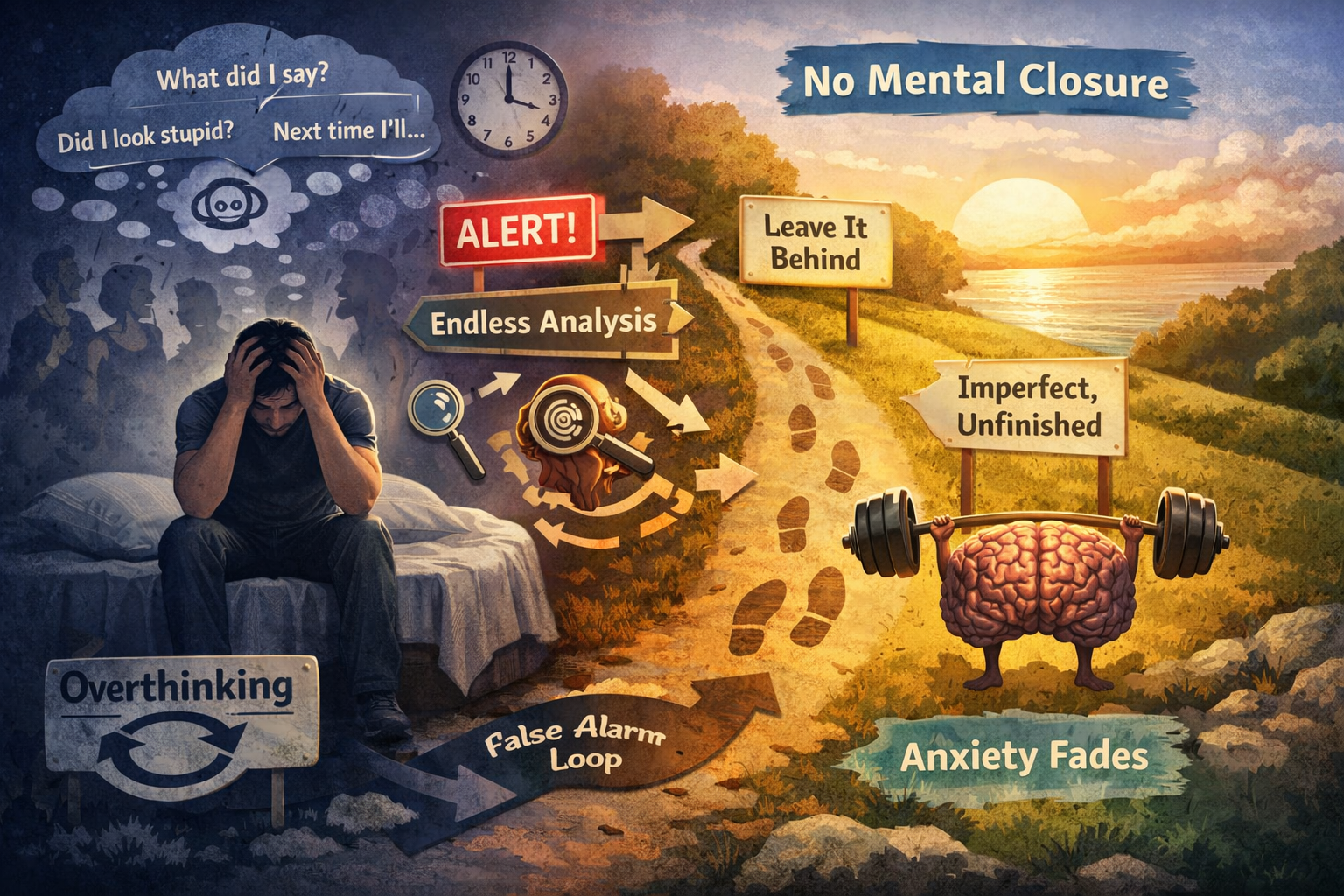

Imagine you walk out of a social gathering. On the surface, it “went fine” — you spoke with people, said what you needed to say, and there were no obvious blunders. Hours later, however, your mind is back at that conversation you had near the snack table. You recall a slight pause before you spoke, the tone of someone’s laugh, the way you smiled. What feels like conscientious self‑improvement is actually a mental loop many people with anxiety know all too well: post‑event rumination. It feels purposeful, like you are strengthening yourself by learning from experience. Yet for individuals with social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), or chronic overthinking, this instinct does not build strength — it maintains anxiety.

This blog post lays out the science behind why over‑analysis feels meaningful but actually sustains anxiety, and what psychological strength truly looks like.

What Post‑Event Rumination Really Is

Post‑Event Processing (PEP) Defined

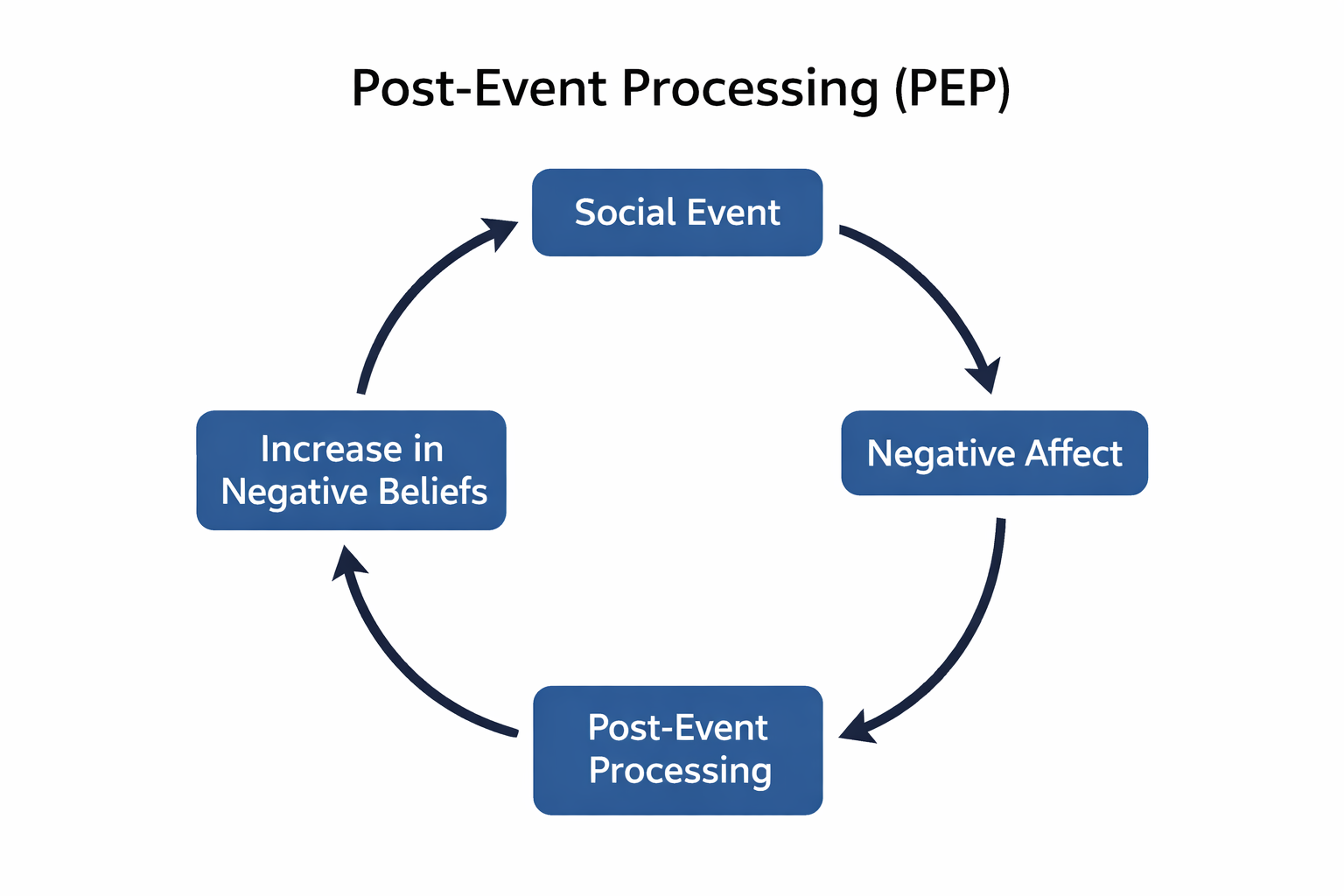

Post-event rumination, often referred to as Post-Event Processing (PEP) in research literature, is the repetitive review of social interactions long after they have occurred. In individuals with anxiety disorders — particularly Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) — PEP can seem rational on the surface, as though you are evaluating “what went wrong” or “what to do differently next time.” However, in reality, it is an emotional process that is triggered by a brain biased toward threat learning rather than genuine self-improvement and constructive reflection. This tendency can lead to persistent feelings of unease and hinder personal growth over time.

Although the thoughts feel analytical, they function emotionally: the goal isn’t to solve a problem but to reduce uncertainty — which the anxious brain mistakes for safety.

Why It’s Common in Social Anxiety and GAD

People with social anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) tend to have a heightened sensitivity to social threat cues and uncertainty in their environments. Their nervous systems prioritize avoiding negative outcomes, leading them to perceive potential dangers where there may be none. In this context, rumination feels like an adaptive strategy aimed at preventing future discomfort or embarrassment. Unfortunately, this kind of repetitive thinking reinforces the salience of perceived threats rather than extinguishing it, ultimately perpetuating the cycle of anxiety and distress instead of alleviating it.

Common Rumination Thoughts

- “Why did I say that? It sounded awkward.”

- “They probably think I’m weird.”

- “I should have responded differently.”

- “I know I messed up — I can feel it.”

- “Next time, I’ll have to plan better.”

Reflection vs Rumination

It is crucial to distinguish between reflection, a calm, structured, and time-limited review with a specific question or goal in mind, and rumination, a repetitive mental loop without resolution that ultimately fuels emotional distress. Reflection is purposefully goal-oriented and constructive; in contrast, rumination is primarily threat-oriented, fixating on perceived dangers and anxieties rather than fostering solutions or positive outcomes. Understanding this difference can significantly impact how individuals manage their thoughts and emotions.

Why “Finding a Solution for Next Time” Backfires

One intuitive way to deal with anxiety would be to analyze what happened in detail and attempt to “fix” it. However, from a threat-learning perspective, this approach often backfires and can lead to increased feelings of anxiety rather than alleviating them. This is because the brain interprets the act of over-analyzing as evidence that there was indeed something wrong or dangerous about the situation, reinforcing feelings of insecurity and self-doubt. Instead of fostering a sense of resolution or closure, this method keeps individuals trapped in a cycle where they continually perceive social interactions as potential threats that require correction. As a result, instead of learning from experiences in a constructive way, individuals might find themselves becoming more anxious during future social situations due to their heightened awareness of perceived flaws and mistakes from past encounters.

The Brain’s Threat‑Learning System

Our brains evolved to detect and learn from danger in our environment. When we painstakingly review past situations, the threat system interprets this process as evidence that something needed to be corrected — even when there was no real danger present at all. This can lead us to mistakenly believe that we are constantly surrounded by threats, which only heightens our feelings of anxiety and insecurity over time.

This creates a learning loop:

- A social interaction occurs.

- The brain searches for signs of threat.

- Rumination identifies potential mistakes.

- The brain encodes these as signals of danger.

- The next event becomes easier to feel anxious about.

Metaphor: False Alarms and Fire Drills

Think of rumination like repeatedly pulling the fire alarm after a false alarm. Each pull reinforces the idea that it might be a real fire, training responders (and your nervous system) to treat every signal as crisis‑worthy. The nervous system never learns “this is safe” — it only learns “this might be dangerous.”

No Mental Closure: The Counter‑Intuitive Mechanism

What “No Mental Closure” Means

No mental closure does not mean suppression of thoughts or denial. It means resisting the drive to complete the story in your mind. Instead of editing and correcting past interactions, you allow the memory to remain cognitively “unfinished,” which gradually reduces the threat value your brain assigns to it.

What It Does Not Mean

- Not suppressing thoughts (which often makes them stronger)

- Not pretending nothing happened

- Not forcing positive reinterpretations

Mental Closure vs No Mental Closure

Mental Closure

- Aims for certainty

- Seeks a “solution”

- Reinforces threat signaling

No Mental Closure

- Accepts uncertainty

- Does not finalize the narrative

- Weakens the brain’s need to rehearse

When we seek mental closure, we’re trying to resolve uncertainty by tying a neat conclusion around an emotionally uncomfortable event. This feels like control, but in anxiety disorders, it actually keeps the brain hyper-focused on perceived threats. In contrast, choosing no mental closure means consciously leaving the experience unresolved — allowing the mind to move on without perfect clarity. Over time, this lack of resolution teaches the brain that discomfort is not danger and that not every social moment needs to be dissected or resolved to be safe.

Imperfection Tolerance as Real Psychological Strength

Trying to be “strong” by striving for perfection or projecting unwavering confidence is still fundamentally a form of control-seeking behavior. In reality, true strength — especially when dealing with anxiety — lies in the ability to tolerate imperfection, awkwardness, and uncertainty without harsh self-judgment or criticism. When you consciously allow yourself to fully experience events as they unfold without internally “correcting” them after the fact, the anxiety circuits receive fewer signals indicating that a threat occurred. This practice ultimately helps reduce overall feelings of distress and promotes emotional resilience over time, allowing you to navigate life’s challenges with greater ease and authenticity.

What Strength Actually Looks Like

- Not needing to replay every social interaction

- Accepting ambiguous memories without resolution

- Not rehearsing “better next time” after successful interactions

- Allowing awkward moments without self‑correction

- Letting thoughts exist without assigning meaning

What CBT and Exposure Research Actually Show

Modern cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure research provide evidence that strength comes from experience, not analysis.

CBT research in anxiety disorders demonstrates that change occurs through restructuring unhelpful patterns during real experiences, not by reviewing them later (Hofmann et al., various).

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) emphasizes drop‑ping safety behaviors and avoidance, but crucially, improvement is not tied to evaluating exposures afterward — it comes from the repeated experience of non‑catastrophic outcomes.

Emotional Processing Theory suggests that emotional networks are modified when feared stimuli are experienced without avoidance or over‑thinking — over‑analysis after the fact does not facilitate processing and may reinforce fear networks.

Improvement in social anxiety and overthinking stems from experiencing uncertainty without review, not from optimizing past events.

Rules That Build Strength Instead of Anxiety

- If the event didn’t harm you, it doesn’t need analysis

- Thoughts that appear hours later are anxiety signals, not insights

- Do not mentally rehearse “next time” after a success

- Notice rumination as it begins and do not complete the story

- Allow memories to sit without finishing them

Conclusion

Psychological strength in the context of anxiety disorders is not about mastering social situations or controlling your internal narrative. It is about tolerating uncertainty and incompleteness. The less meaning and threat you assign to past social events, the faster anxiety circuits diminish their hold. Strength is not control — strength is acceptance that not every mental loop needs closure.

References

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive‑behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well‑being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

Hofmann, S. G., et al. (Various). CBT for anxiety disorders: A comprehensive evidence base. Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Research on Post‑Event Processing (PEP) in Social Anxiety (Various empirical studies in cognitive psychology and anxiety literature).