Many people with social anxiety or anxiety disorders believe that recovery hinges on becoming socially smooth, confident, and “successful” in interactions. You might think: if only I could win at every conversation, never feel awkward, and always impress others, then my anxiety would go away. This belief feels intuitive because it mirrors how performance works in school, sports, or work: practice plus success equals mastery. However, social anxiety isn’t cured by social performance. It’s maintained by psychological processes that reward certainty, control, and avoidance, not by flawless social results. In this post, we’ll explain why you don’t need to excel socially to recover, and why chasing performance-based recovery actually reinforces anxiety.

How Anxiety Disorders Work: Neurobiology and Cognition

Anxiety isn’t a simple fear of social situations, it’s a nervous system pattern shaped by cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms that favor threat detection and certainty over ambiguity. Key mechanisms include:

Threat Detection and the Amygdala

- The amygdala flags potential threats. In anxiety disorders, it becomes hypersensitive to ambiguous social cues.

- Neutral or uncertain social signals are interpreted as threats rather than harmless stimuli.

Intolerance of Uncertainty

- People with anxiety struggle with situations that are unpredictable or ambiguous.

- This intolerance drives rumination and post-event processing, as the brain tries to reduce uncertainty after social interactions.

Cognitive Patterns That Maintain Anxiety

- Safety behaviors: things you do to prevent perceived catastrophe (over-rehearsing what to say, monitoring your behavior in real time, asking for reassurance).

- Post-event processing: replaying conversations endlessly to judge performance or find flaws.

These processes don’t disappear when you do well socially. They persist because the nervous system prioritizes certainty and control over actual outcomes. Anxiety isn’t maintained by social failure, it’s sustained by the belief that you must control how events go and what others think.

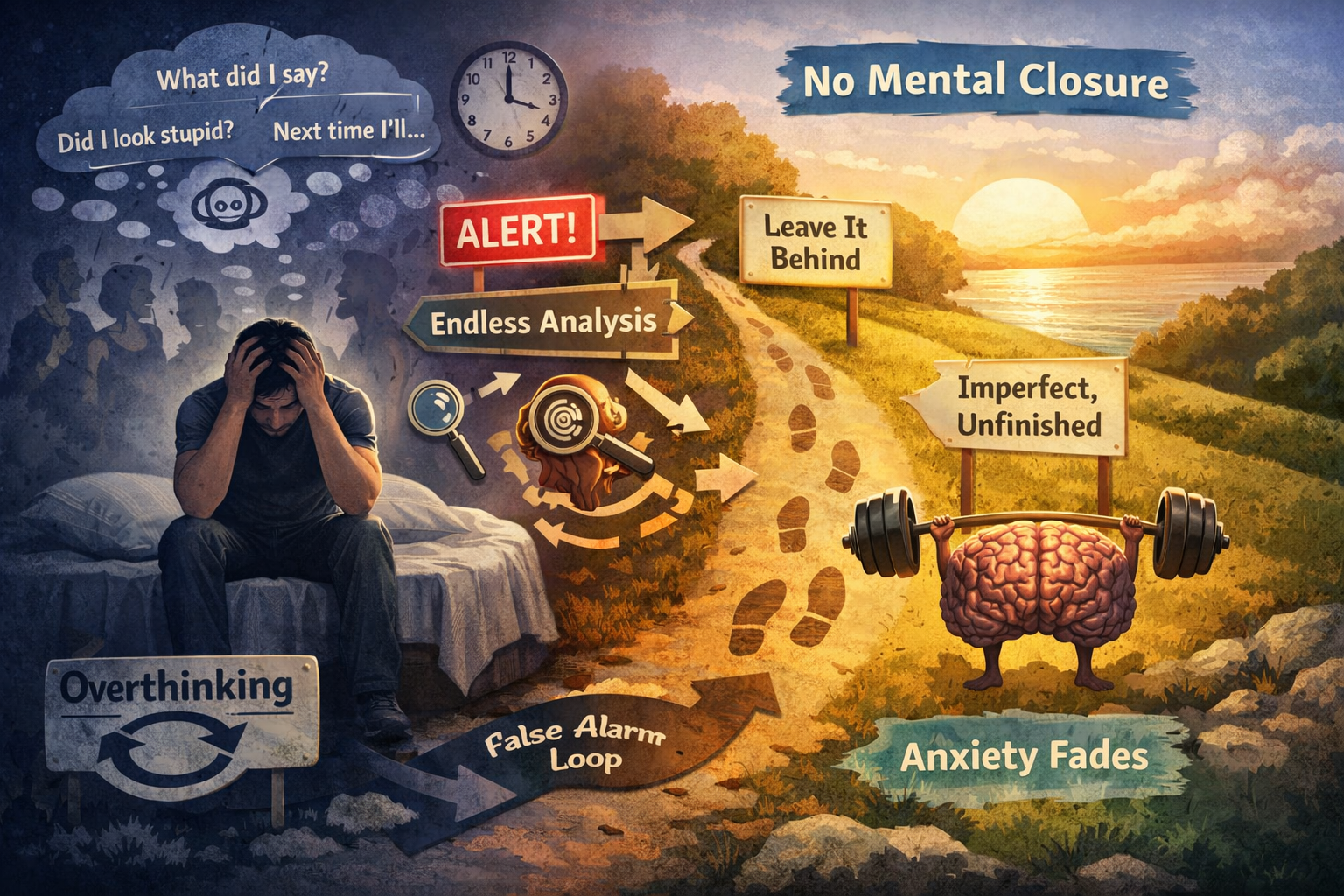

Why “Success-Based Recovery” Backfires

The idea that you need to succeed socially to heal can actually reinforce anxiety. Here’s how:

1. Performance Monitoring

Constantly checking how you’re doing in conversations keeps attention on internal states rather than the actual interaction.

- You notice your heart rate, what you said, and how you sounded

- This increases self-focus and anxiety even if the interaction was neutral or positive

2. Reassurance-Seeking

Looking for confirmation that you did well, from yourself or others, becomes a safety behavior that prevents learning that uncertainty is tolerable.

3. Rumination and Post-Event Analysis

After a social event, you might:

- Replay every sentence

- Look for things you could have said better

- Judge every pause as a failure

Even when objectively fine, this post-event rumination keeps the threat alive and conditions your nervous system to expect discomfort next time.

These behaviors are reinforced because they temporarily reduce anxiety (it feels safer to analyze and fix), but they prevent long-term learning that uncertainty doesn’t equal danger.

No Mental Closure and Acceptance of Imperfection: Evidence-Based Mechanisms

Two key concepts from modern anxiety treatment are especially important: No Mental Closure and Acceptance of Imperfection. These are not motivational slogans, they are mechanisms grounded in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure and response prevention (ERP), and inhibitory learning theory.

No Mental Closure

This means letting social events end without replaying, explaining, fixing, or judging them.

- Instead of thinking “I should have said X,” you allow the memory to settle without commentary.

- Avoids reinforcing cognitive loops that make your brain treat the event as unfinished threat processing.

Acceptance of Imperfection

Rather than trying to eliminate awkwardness or mistakes, you allow them to occur without correcting them.

- Accept that social interactions are inherently unpredictable.

- Imperfection doesn’t mean threat, it means human.

How These Concepts Fit Into Evidence-Based Treatment

- CBT works by identifying and modifying unhelpful thought patterns and behaviors.

- ERP involves facing anxiety-provoking situations without engaging in safety behaviors.

- Inhibitory learning theory suggests that learning happens not when anxiety decreases during practice, but when you disconfirm threat expectations, letting anxiety be present and not trying to fix it.

These approaches all emphasize learning from exposure without correction, not optimizing performance.

What to Do After a Social Interaction

Here are practical, evidence-aligned steps to promote recovery:

What to Stop Doing

- Avoid analyzing every word you said

- Stop trying to “decode” others’ reactions

- Don’t seek reassurance about how you did

What to Allow

- Uncomfortable thoughts to fade naturally

- Gaps in conversations without filling them mentally

- Ambiguity about others’ judgments

What Discomfort to Tolerate

- Momentary awkwardness

- Uncertainty about how you came across

- Internal sensations without trying to control them

Signals of Real Progress

- Less post-event replaying

- Reduced urgency to fix what happened

- More ability to accept “I don’t know” about others’ thoughts

- Feeling more grounded even if nervous

What Recovery Actually Looks Like

Recovery is not constant confidence or perfect social fluency. It looks like:

- Reduced urgency to escape or fix social situations

- Less post-event rumination and mental reviewing

- Greater tolerance for ambiguity and imperfection

- Emotional flexibility rather than rigid performance goals

You don’t need to be fearless or charming, you need to be willing to face uncertainty without control strategies.

Myth vs. Fact

Myth: You must succeed socially to heal.

Fact: Recovery comes from retraining how your brain responds to uncertainty and discomfort.

Myth: Good social experiences cure anxiety.

Fact: Without changing safety behaviors and rumination, even positive experiences can be misinterpreted and forgotten.

Myth: Confidence equals recovery.

Fact: Psychological flexibility and tolerance for imperfection are stronger predictors of long-term change.

Conclusion

The belief that you must perform well socially to recover from anxiety feels intuitive because it mirrors everyday achievements. But anxiety disorders are maintained by avoidance, control strategies, and intolerance of uncertainty, not by social mistakes or successes. Real recovery comes from learning that you can tolerate discomfort, accept imperfection, and let experiences unfold without needing mental closure or perfect performance. Strength isn’t about how successful you appear, it’s about how flexible your mind and nervous system can become.

References

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia.

- Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of social anxiety.

- Hofmann, S. G., & Otto, M. (CBT for Anxiety Disorders).

- Craske, M. G., et al. (2014). Inhibitory learning approach to exposure therapy.

- Literature on post-event processing and intolerance of uncertainty in anxiety disorders.