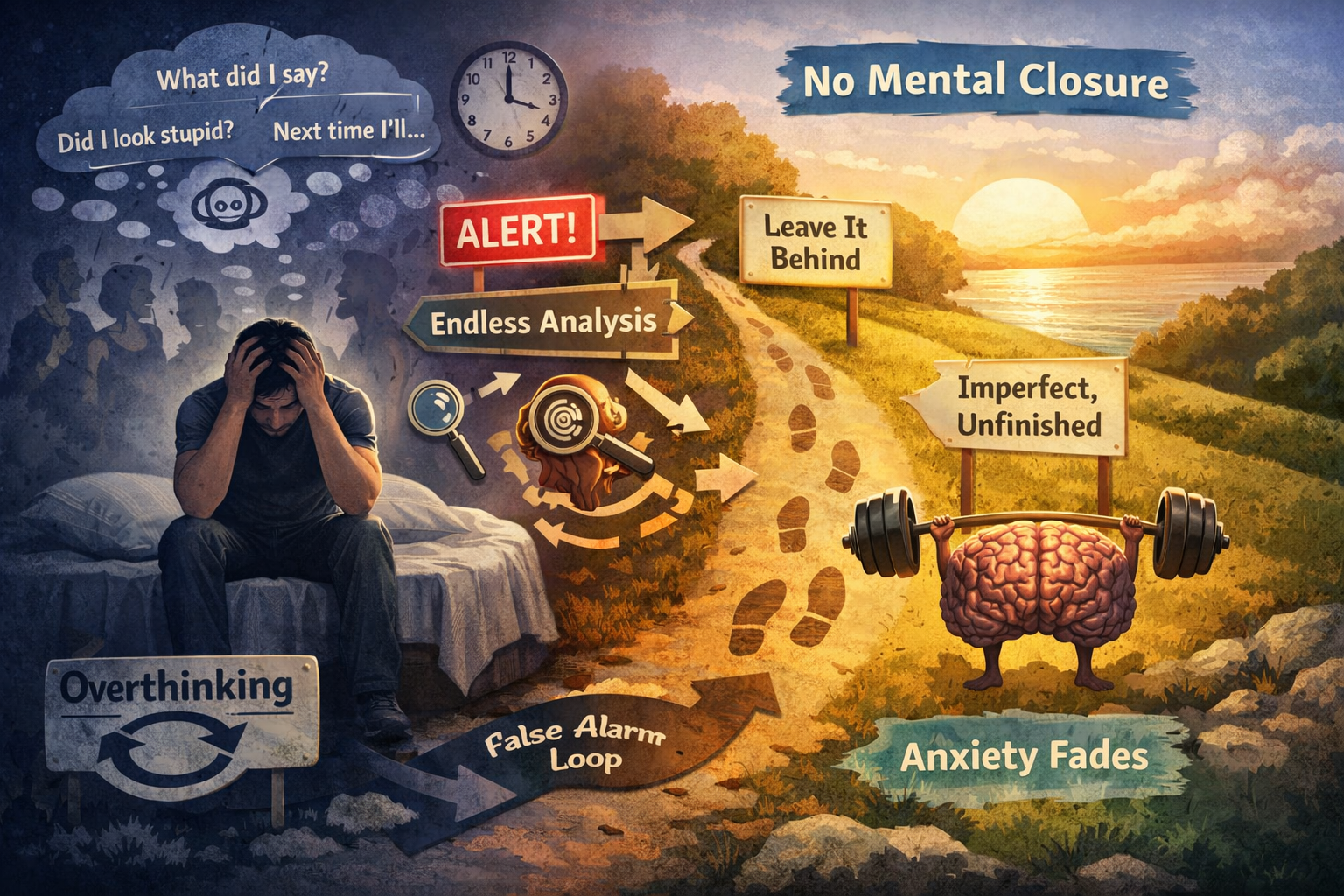

Post‑Event Rumination, also called post‑event processing in the scientific literature, is a cognitive pattern in which a person repeatedly replays and analyzes a past event, especially social interactions, long after the event has ended. On the surface it feels thoughtful: you’re “learning” from what happened. But in many cases this processing isn’t about learning, it’s about anxiety trying to regain certainty and control. Rather than reducing future worry, rumination solidifies anxiety pathways, keeps the nervous system on alert, and paradoxically increases distress over time.

Post‑Event Rumination is especially common in Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). People with social anxiety often replay conversations that objectively “went fine,” scrutinizing their words, nonverbal behavior, or perceived awkwardness. Individuals with generalized anxiety may ruminate about a range of concerns, from interactions at work to choices made earlier in the day, long after the situation has passed.

What Rumination Is, and What It Is Not

It’s important to distinguish between productive reflection and pathological rumination.

Productive reflection is:

- Focused on clear questions (e.g., “What did I learn?”)

- Limited in time and intensity

- Oriented toward specific, testable adjustments

- Detached from fear of judgment or threat

Pathological rumination, in contrast, is:

- Open‑ended (“What if I said it wrong?”)

- Repetitive and intrusive

- Driven by anxiety’s need for certainty

- Designed to reduce fear in the moment rather than to improve future outcomes

Key Difference:

Productive reflection solves problems.

Rumination avoids uncertainty.

Why Rumination Happens Later, The Neuroscience and CBT of Delay

One puzzling phenomenon about rumination is that it often doesn’t start immediately after the event, it begins hours later, sometimes in bed at night. There’s a reason for this timing.

1. Threat Learning and Memory Consolidation

Emotional memories are processed and consolidated during downtime, especially when the brain shifts from active task mode to internal processing. The amygdala (a threat‑detection hub) flags emotionally salient moments, and the hippocampus embeds them into memory. This means that the brain may “revisit” an event after the fact, especially if it judged that event as uncertain or potentially threatening.

2. Intolerance of Uncertainty

In anxiety disorders, intolerance of uncertainty is a core maintaining factor. When the brain encounters a situation lacking 100% certainty (“Did I say the wrong thing?”), it tries to fill gaps later with rumination. This is not about solving anything; it’s about attempting to erase uncertainty, which is neurologically impossible.

3. Amygdala Activation and Error‑Correction Bias

The amygdala supports vigilance and scanning for threat. When activated during a social situation, it leaves a cognitive trace that the brain continues to review post‑event. From a cognitive bias standpoint, the brain tends to overemphasize negative or ambiguous social signals, the negativity bias, leading to replay that focuses on potential mistakes rather than neutral or positive aspects.

Essentially, rumination is anxiety’s second attempt to regain control, but it uses the same fear circuits that reinforced the original anxiety, not the rational learning circuits.

No Mental Closure and Acceptance of Imperfection

Two concepts central to understanding and overcoming rumination are No Mental Closure and Acceptance of Imperfection.

No Mental Closure

Closure is a myth in anxiety processing. The brain doesn’t need “answers.” What it needs is tolerance of uncertainty. Trying to close the loop by revisiting every detail is not reflective thinking, it’s avoidance in disguise.

Acceptance of Imperfection

Perfection is the enemy of psychological resilience. When we allow ourselves to leave events unanalyzed and accept that performance was good enough, we:

- Break the cycle of threat reinforcement

- Reduce vigilance in future social situations

- Decrease activation of fear‑based neural networks

Importantly, allowing ambiguity weakens anxiety over time. This is the opposite of what anxiety wants you to do (which is to churn and check and revisit).

The Counterintuitive Belief: “Rumination Builds Resilience”

Many people believe that analyzing what went wrong will make them better next time. CBT and Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) principles clearly dismantle this:

- Rumination is a Safety Behavior

- A safety behavior is anything you do to reduce anxiety in the short term but that prevents true learning.

- Rumination feels helpful because it immediately reduces uncertainty (negative reinforcement).

- Negative Reinforcement Strengthens the Habit

- Every time rumination reduces anxiety in the moment, it reinforces the habit.

- This makes it harder to resist next time, even though the long‑term effect is worse.

- False Problem‑Solving

- Rumination masquerades as problem‑solving but does not test hypotheses.

- True problem‑solving requires experimentation, not review without action.

In short: Rumination does not build resilience. It builds avoidance and sensitivity to threat.

What Not to Do After a Social Event

After a social situation, avoid the following:

- Replay the event in your head repeatedly

- Ask open‑ended questions (“What did I do wrong?”)

- Seek reassurance from others to “confirm” how you did

- Review your performance before sleeping

- Create “what‑if” scenarios in your imagination

- Assign exaggerated meaning to small details

These behaviors feed anxiety.

What Actually Builds Psychological Strength

Instead of rumination, the following strengthen resilience:

1. Experience Without Mental Correction

Let events be events. Leave them unanalyzed unless there is clear, constructive information.

2. Tolerate Ambiguity

Notice uncertainty and allow it without trying to eliminate it.

3. Resist Mental Reassurance

Don’t seek confirmation from others or from your own inner critic.

4. Behavioral Experimentation

If there is something you want to adjust, define a specific, actionable experiment, with measurable behavior, not open‑ended evaluation.

5. Mindful Redirection

When you notice your mind drifting into rumination, gently redirect to the present moment or a specific task.

Real‑World Illustrations (Conceptual)

- After a team meeting that went smoothly, a person lies awake replaying every sentence, worrying they sounded boring, despite positive feedback. This rumination reinforces the idea that social outcomes are threats, not neutral or positive experiences.

- After a party where several people laughed and seemed friendly, someone reimagines an awkward pause as evidence of rejection. The resulting loop of rumination fuels avoidance of future events.

These examples show how rumination magnifies threat and embeds anxiety rather than reducing it.

Summary: Strength Comes from Disengagement, Not Analysis

Post‑Event Rumination feels smart, it feels like review, analysis, and improvement. But scientifically and clinically, it functions as a threat‑reinforcing loop driven by anxiety’s intolerance of uncertainty. Real psychological strength is built by disengaging, tolerating ambiguity, and allowing imperfect performance to stand without mental correction. Let go of the need to replay, and let the nervous system learn that the world is often neutral, not threatening.

References

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment.

- Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive‑behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy.

- Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognition and Emotion.

- Gross, J. J. Emotion Regulation.

- CBT and ERP clinical literature on anxiety maintenance and avoidance behaviors.