Why “Feeling Calm” Isn’t the Answer

Most people struggling with anxiety have at least one strategy in common: they are constantly trying to feel calm. They hunt for relaxation, avoid triggers, suppress uncomfortable sensations, and seek reassurance that everything is “okay.” On the surface, these strategies seem sensible , who wouldn’t want less anxiety? But decades of research suggest something counterintuitive: the relentless pursuit of calm can actually maintain or amplify anxiety over time.

This apparent contradiction isn’t just clinical observation, it’s supported by empirical work on experiential avoidance, emotional suppression, and the neuroscience of worry and threat systems. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) reframes anxiety not as a problem to be eliminated, but as a human experience to be engaged with differently. The ACT skill of Acceptance and Willingness offers a pathway toward lasting reductions in anxiety that doesn’t depend on feeling calm.

The Control-Based Trap: Why Anxiety Persists

Humans are wired to avoid pain and seek safety. Anxiety feels bad, so we try to:

- Suppress anxious thoughts and sensations

- Avoid people, places, or situations that trigger discomfort

- Seek reassurance from others or information sources

- Over-regulate emotions with distractions, substances, or perfectionistic planning

These are all control-based strategies. They attempt to eliminate or prevent anxiety rather than relate to it in a flexible way.

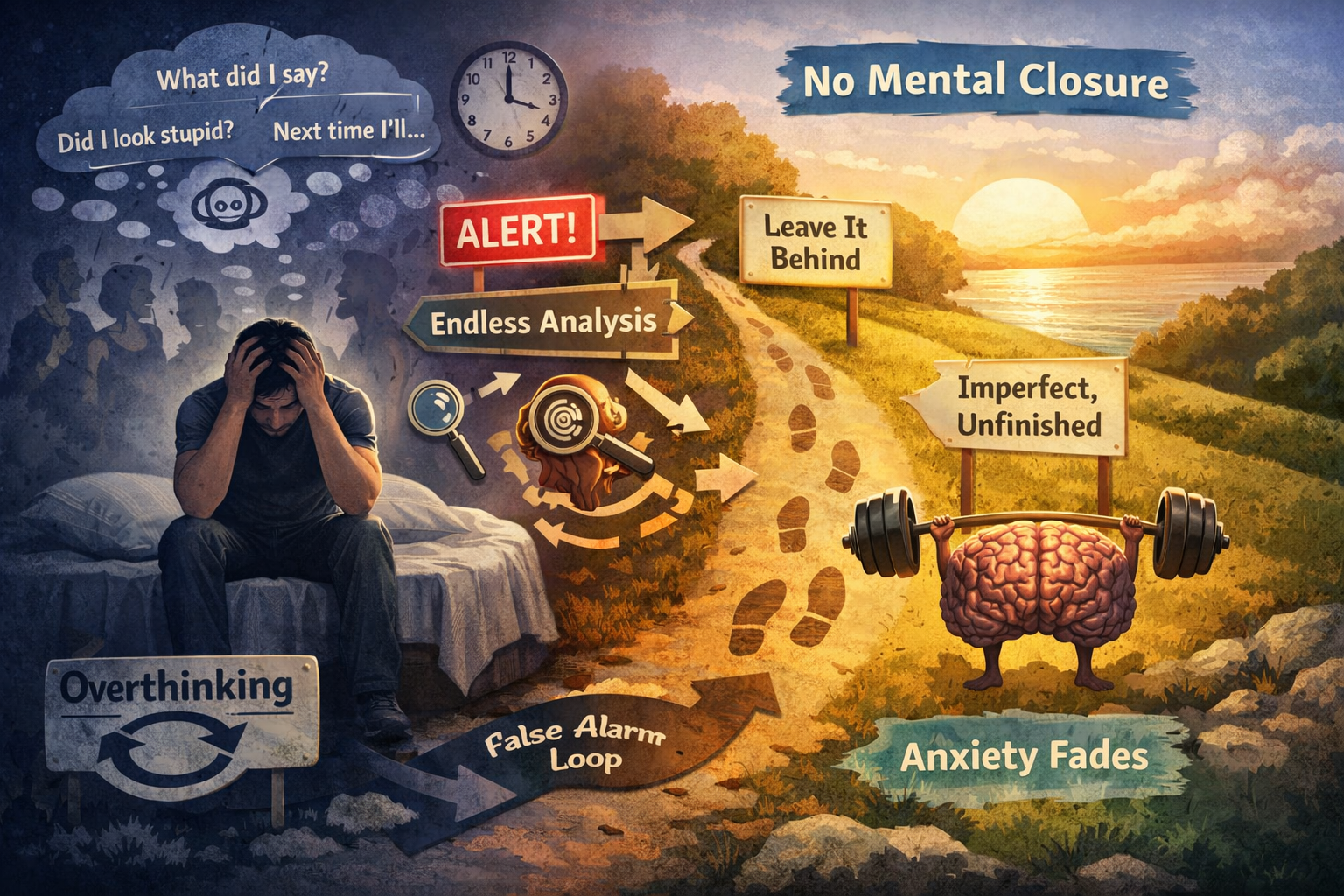

But here’s the paradox:

Attempts to control anxiety often lead to greater frequency and intensity of anxious responses over time. This happens because:

- Suppressed thoughts rebound with greater salience (Wegner’s ironic process theory)

- Avoidance prevents learning that feared outcomes are often tolerable

- Reassurance-seeking temporarily reduces distress but strengthens reliance on external validation

Neuroscience studies show that when we engage the brain’s threat systems with control and suppression efforts, we reinforce neural patterns associated with vigilance and avoidance rather than flexibility. Efforts to force calmness engage the prefrontal control regions in opposition to limbic signals, creating internal conflict that paradoxically sustains anxiety.

A Shift in Perspective: What Is ACT?

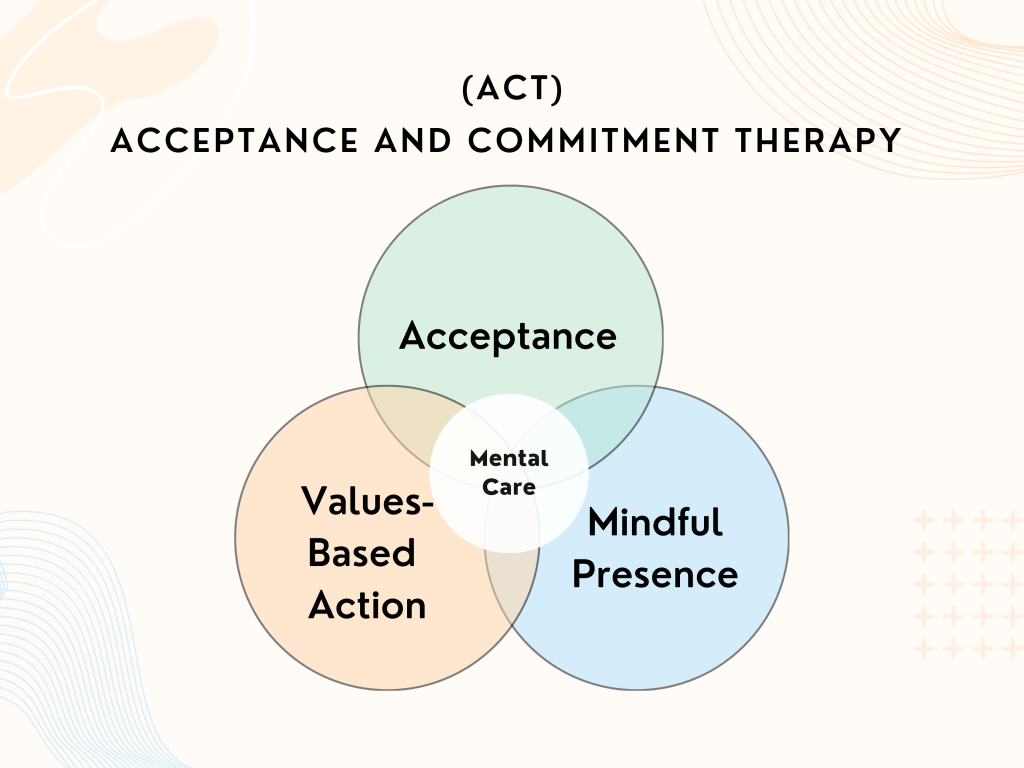

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a form of behavioral psychotherapy grounded in contextual behavioral science (Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson, 1999; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda & Lillis, 2006). ACT isn’t about feeling calm, it’s about increasing psychological flexibility, the ability to be present with whatever arises and choose actions that align with personal values.

Psychological flexibility has three core processes:

- Acceptance and Willingness – Making room for uncomfortable internal experiences without trying to change their form or frequency

- Mindful Presence – Observing internal events nonjudgmentally in the present moment

- Values-Based Action – Pursuing meaningful behavior even in the presence of discomfort

Research indicates that psychological flexibility is associated with lower anxiety, higher well-being, and better emotional regulation (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010).

Acceptance and Willingness: The Core ACT Skill

At its essence, acceptance in ACT refers to a willingness to contact internal experiences such as thoughts, sensations, and emotions without unnecessary struggle. This isn’t passive resignation, it’s an active stance of engagement.

Acceptance means:

- Allowing feelings to have a place in your experience

- Not spending excessive energy trying to eliminate or suppress anxiety

- Creating space for internal experiences while acting in the direction you care about

Willingness does not mean liking anxiety. It means not wasting energy fighting it.

Why Acceptance Reduces Anxiety

- Reduces Avoidance

When you stop battling anxiety, you naturally engage more with life. Avoidance, not anxiety itself, tends to maintain and fortify fear circuits. - Interrupts Suppression Cycles

Attempts to suppress thoughts increase their cognitive priority. Acceptance reduces this rebound effect. - Enhances Learning

When you experience feared sensations without avoidance, the brain updates predictions about threat and safety, a form of natural exposure.

Misconceptions About Acceptance

Misconception 1: “Acceptance means giving up.”

Reality: Acceptance is about acknowledging what is present so you can act effectively. It’s not resignation; it’s clarity.

Misconception 2: “Acceptance means liking anxiety.”

Reality: You don’t have to enjoy anxiety to accept it. You simply stop fighting it so compulsively.

Misconception 3: “I must feel calm to function.”

Reality: Functioning with discomfort is often more effective than struggling for comfort.

What Acceptance Looks Like in Real Life

Here are a few descriptions of how acceptance shows up, without clinical instructions:

- Noticing the physical sensations of anxiety without immediately trying to push them away

- Acknowledging anxious thoughts as thoughts, not facts or threats

- Choosing to engage with a valued activity even when anxiety is present

- Recognizing that the attempt to “fix” your feeling isn’t necessary for meaningful action

In these moments, anxiety might still be present, but it no longer dominates decision-making or behavior.

Why Anxiety Reduces as a Byproduct, Not a Goal

When acceptance becomes the context for experience, anxiety no longer needs to be controlled or eradicated. Instead:

- Worry is seen for what it is (a mental event, not a threat)

- Avoidance patterns weaken

- Values-guided action increases

- Neural systems adapt through learning rather than suppression

In short, psychological flexibility grows, and anxiety diminishes on its own terms.

References

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes.

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health.