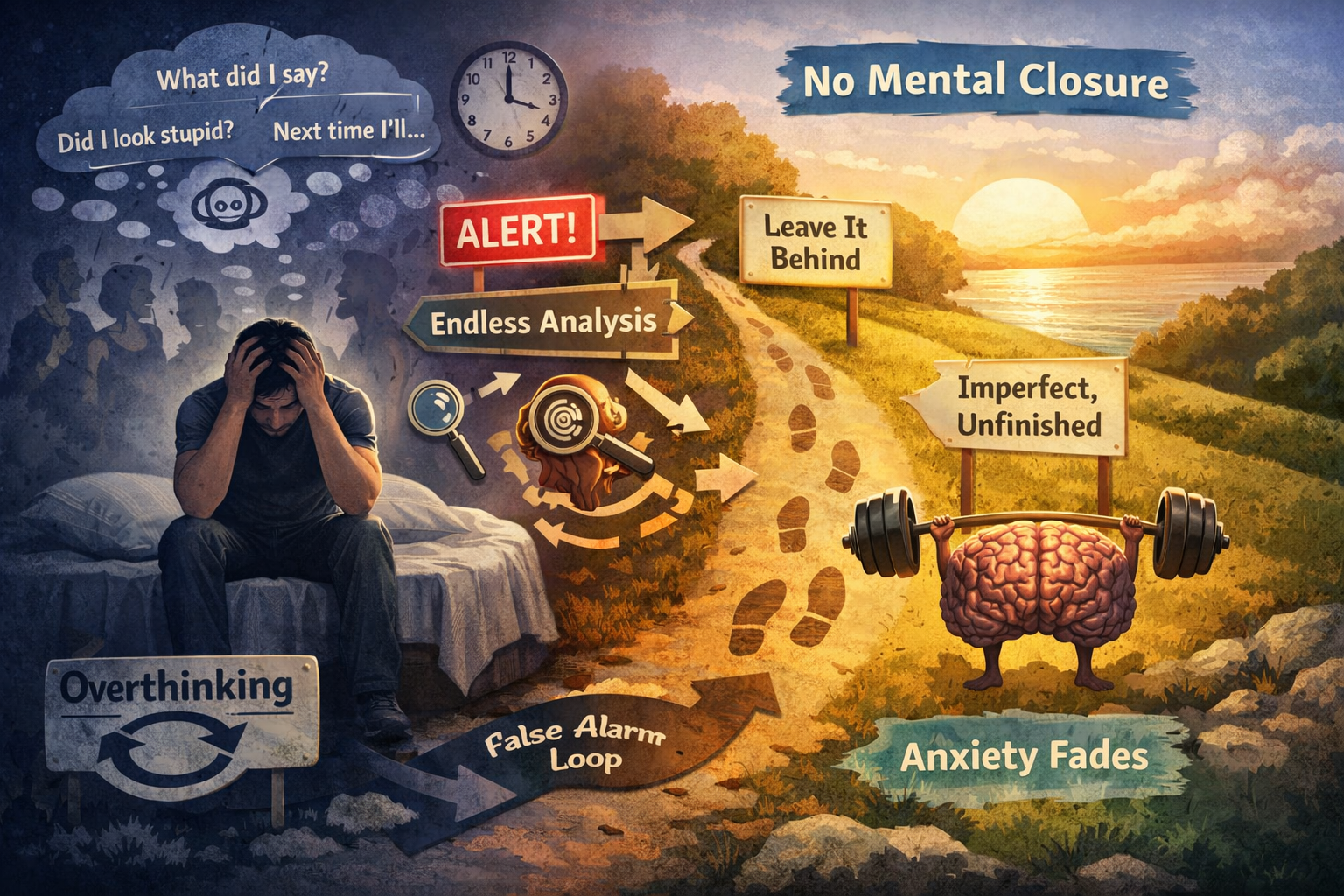

Many adults with social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or chronic overthinking know this pattern all too well: you leave a social interaction and on the surface, nothing “bad” happened, no humiliation, no conflict, no overt rejection. Yet hours later your mind replays every moment. You scrutinize what you said, how someone looked at you, what you should have said, or haven’t said. This feels purposeful and instinctively appealing, as if dissecting the event is preparation for doing better next time. In the context of anxiety, however, this instinct is misleading. The urge to analyze, explain, or find a solution after the fact is not a pathway to psychological strength. In anxiety disorders, it maintains the problem by reinforcing the brain’s threat learning rather than resolving uncertainty.

What Post‑Event Rumination Really Is

Post‑Event Processing (PEP) in Research Terms

Post‑event rumination — often referred to as Post‑Event Processing (PEP) in the anxiety literature, is a repetitive, detailed review of a social situation after it has ended. In social anxiety disorder (SAD), this process often focuses on perceived mistakes, threats of negative evaluation, or imagined shortcomings in social performance. PEP has been highlighted as a core maintenance factor in leading cognitive models of social anxiety, including the influential work of Clark & Wells (1995) and Rapee & Heimberg (1997) that emphasize biased cognitive processing after social events.

Although it feels analytical, PEP functions emotionally: it is a form of threat rehearsal. Individuals with social anxiety engage in more PEP than non‑anxious individuals, and higher levels of PEP are associated with greater social anxiety symptoms over time.

Why It Seems Rational but Isn’t

Rumination feels like problem‑solving because it superficially resembles reviewing performance and planning improvements. But unlike healthy reflection, PEP doesn’t occur with a clear question or endpoint. Instead, it becomes repetitive, intrusive, and self‑focused, and it reinforces negative self‑appraisal and threat salience.

Common Post‑Event Rumination Thoughts

- “I sounded awkward when I spoke.”

- “They must have thought I was strange.”

- “I missed chances to say something witty.”

- “Why didn’t I say the ‘right’ thing?”

- “Next time I have to plan better.”

Notice that these thoughts are not anchored in objective evidence, but in perceived threat and uncertainty — the fuel for anxiety.

Reflection vs. Rumination

A key distinction from CBT and learning theory is that healthy reflection is goal‑oriented and time‑limited, whereas rumination is repetitive, self‑perpetuating, and emotionally driven without a clear resolution goal.

Why the Anxious Brain Seeks Explanations After the Fact

The nervous system prioritizes learning from threat. In evolutionary terms, it is adaptive to encode and respond to real danger. But in chronic anxiety, the brain’s threat‑learning circuits — involving structures like the amygdala — become over‑sensitive to uncertainty and potential social evaluation. Instead of integrating evidence that a non‑harmful event was safe, rumination reinforces the possibility of threat. The very act of repeatedly focusing on “what happened” trains the brain to treat ambiguous or harmless social situations as if they might have been threatening — a feedback loop that reinforces anxiety instead of dissolving it.

Neurologically, repetition strengthens associative pathways. Each rumination cycle reactivates threat networks, strengthening their accessibility in memory and anticipation. Over time, this biased encoding increases the likelihood that future social events will trigger anxiety — even if nothing objectively harmful occurred.

Why “Mental Closure” Is Attractive but Counter‑Therapeutic

After a socially uncertain or ambiguous event, the brain naturally seeks closure. This is a basic cognitive drive: to resolve open-ended or unclear experiences into a structured, complete narrative. When something feels unresolved, especially in the social domain, the anxious mind often reacts by scanning for meaning, replaying interactions, and interpreting subtle cues. This process is not random; it stems from the brain’s attempt to reduce internal tension by achieving certainty. Closure gives the illusion of control, which can feel psychologically safer than sitting with not knowing. In anxiety disorders, this drive is heightened. Every interaction becomes a potential source of threat that needs to be interpreted and neutralized through explanation.

In individuals with anxiety, mental closure takes the form of detailed internal analysis. The brain generates interpretations, explains facial expressions, tone of voice, pauses, or one’s own behavior with a kind of mental magnifying glass. While this feels like resolution, it is in fact an emotional regulation strategy disguised as cognitive insight. Rather than increasing understanding, it increases salience, drawing more attention and emotional weight to the perceived flaws or social missteps.

Studies in emotion regulation and social anxiety consistently show that this style of post-event analysis does not reduce fear but strengthens neural associations between social ambiguity and personal threat.

By seeking closure through repeated internal explanation, the brain unintentionally signals to itself that the event was important, emotionally charged, and potentially dangerous. This prevents it from learning a more adaptive response: that ambiguity and imperfection can be tolerated without harm. When social situations are left without obsessive analysis, the memory of them fades into emotional neutrality. But when they are revisited over and over in search of meaning, the mind keeps the emotional charge alive. In this way, striving for closure paradoxically sustains the fear response and reinforces the idea that social interactions are threats to be managed, rather than lived through and left alone.

“No Mental Closure” — A Counter‑Intuitive but Evidence‑Based Principle

What No Mental Closure Means

No mental closure is not about avoiding thought, suppressing memory, or dismissing your experience. It is about not completing the story in your mind. Rather than searching for a definitive explanation or meaning after a social event, no mental closure involves allowing the memory to remain open and unpolished, acknowledging uncertainty without seeking to “fix” it.

Why This Weakens Threat Learning

When the anxious brain stops finding threats or final answers after social events, it starts learning that uncertainty itself isn’t dangerous. By not resolving the discomfort, the brain gradually decouples ambiguity from threat. Over time, this reduces the emotional weight of social situations and weakens the habit of mental rehearsal. The brain stops treating uncertainty as a problem to fix — and starts treating it as something safe to leave alone.

Healthy Reflection vs. Rumination

Understanding the difference between healthy reflection and pathological rumination is essential for anyone managing social anxiety, generalized anxiety, or chronic overthinking. At first glance, they can look similar — both involve thinking about past events. But their functions, emotional tone, and outcomes are fundamentally different.

Healthy reflection is a deliberate, structured process with a clear objective. It typically arises from a specific intention — for example, reviewing whether a particular goal was met or identifying a single area for improvement in a balanced, non-judgmental way. It is time-limited, usually brief, and does not trigger significant distress. Most importantly, it ends with a decision or a sense of closure. Healthy reflection helps consolidate learning when used in moderation and directed by curiosity rather than fear.

Pathological rumination, by contrast, is repetitive, intrusive, and emotionally charged. It arises not from a clear question, but from unresolved discomfort or uncertainty. The process is open-ended and often circular — the same thoughts return again and again, often becoming more exaggerated or distorted over time. Rather than clarifying anything, rumination deepens self-doubt and reactivates anxiety. It is not about learning; it is about trying to relieve the intolerable feeling of “not knowing” — often by imagining worst-case scenarios or mentally rehearsing alternative outcomes. This mental behavior keeps the brain in a state of perceived threat, even in the absence of external danger.

In summary:

- Healthy reflection supports adaptive learning and ends naturally

- Rumination fuels anxiety and becomes a compulsive mental habit

- Reflection is guided by clarity; rumination is driven by emotional urgency

- Reflection looks at outcomes; rumination fixates on self-evaluation and imagined flaws

Distinguishing between the two — and learning to disengage from rumination — is a critical part of reducing anxiety’s grip on daily life.

Allowing Imperfection: The Real Mechanism of Strength

Trying to optimize every reaction, response, or impression after the fact — even after a successful event — is another form of control‑seeking. In anxiety disorders, this reinforcing of “gotta do better” maintains vigilance for threat rather than allowing habituation to safety. True stability comes from viewing social events as neutral or non‑threatening, not as tests to be graded and corrected.

What Strength Actually Looks Like

- Accepting that a social event was not harmful without reviewing it endlessly

- Not mentally rehearsing “better” responses after success

- Being able to let ambiguous memories sit without investigation

- Redirecting attention to ongoing life tasks instead of internal analysis

Practical Alternatives to Rumination (Educational, Not Therapeutic)

Instead of engaging in repetitive review:

- Label the Process: Recognize the urge to analyze as rumination, not problem‑solving

- Refuse Extended Analysis: When the mind begins replaying, consciously do not complete the arc of meaning

- Redirect Attention: Shift attention to ongoing tasks rather than internal narratives

- Behavioral Continuation: Continue engaging in valued activities without internal “review”

These tendencies harness the same principles behind inhibitory learning and exposure research — experiences that occur without reinforcement of fear networks lead to lasting reductions in anxiety.

Common Misconceptions and Why They Backfire

“I’m just trying to be stronger next time.”

This reasoning presumes that post‑event analysis will lead to improvement. However, the anxious brain interprets this as evidence that the prior event was uncertain or threatening, thus reinforcing anxiety and alertness rather than promoting stability. In essence, post‑factum optimization reintroduces threat learning instead of allowing the brain to encode safety and uncertainty tolerance.

“If I don’t go over it, I might make the same mistake again.”

This belief assumes that self-review is necessary for learning. But in anxiety disorders, the brain already overestimates risk and exaggerates mistakes. Rumination doesn’t clarify, it distorts. Replaying the event increases the likelihood that neutral or successful interactions will be coded as failures, reinforcing avoidance and hypervigilance rather than genuine learning.

“I need to understand what went wrong so I can avoid it.”

This reflects the anxious brain’s demand for certainty. The problem is, in many social situations, nothing objectively did go wrong, yet the need to find a problem creates one. This reinforces the idea that every interaction must be analyzed for hidden danger. In doing so, the brain never learns that it’s safe to leave events unexamined and incomplete, a key ingredient in long-term anxiety reduction.

“Thinking it through helps me feel in control.”

Control-seeking is a natural response to anxiety, but mental control through rumination is a false sense of safety. It creates the illusion of mastery while keeping the brain locked in a hyper-alert state. The more control you try to exert through thought, the more your brain stays convinced that something needs managing, reinforcing the anxiety loop rather than breaking it. True stability comes from reducing the need for control, not increasing it.

Conclusion

The core mechanism by which anxiety decreases over time is not repeated analysis of past events but tolerance of uncertainty, imperfection, and lack of mental closure. In anxiety disorders, repeatedly reviewing neutral or successful social interactions reinforces threat networks rather than extinguishing them. Letting non‑harmful events remain cognitively “unfinished” is not avoidance, it is adaptive learning that reduces the emotional significance of ambiguous social cues. Ignoring what happened after the fact is not avoidance but de‑emphasizing threat and fostering psychological stability.

References

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive‑behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756.

Brozovich, F. A., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post‑event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 891–903.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well‑being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

Edgar, E. V., et al. (2024). Post‑event rumination and social anxiety: Systematic review and meta‑analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research.