The Paradox of Improvement in Anxiety

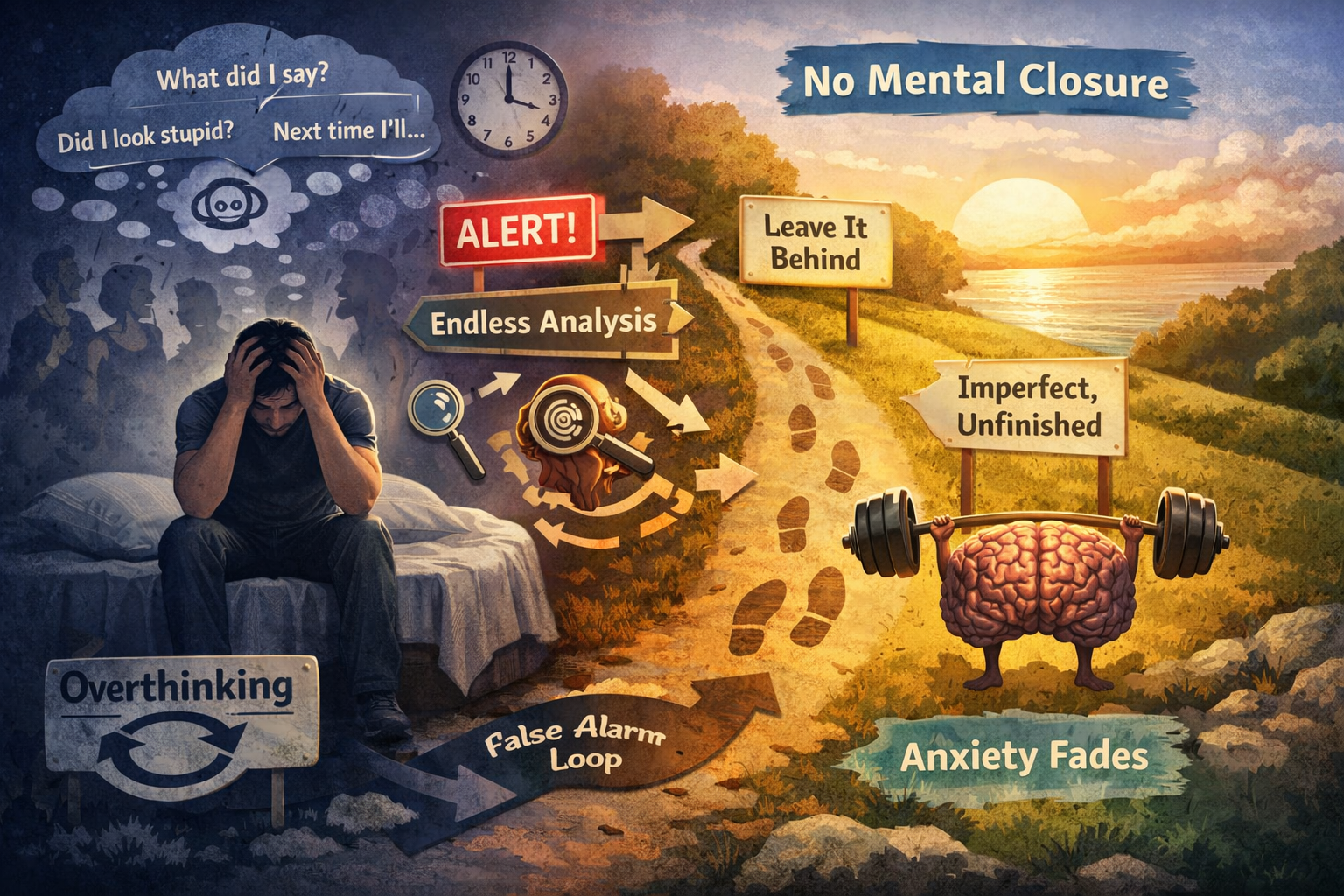

Many adults with social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), chronic overthinking, and high self‑monitoring tendencies carry a persistent internal belief: if I can just understand what went wrong after a social event and plan a better reaction next time, I’ll feel safer, more confident, and stronger. At first glance, this belief seems rational and even adaptive. However, decades of cognitive and neuroscientific research show that in anxiety disorders this instinctive drive to analyze, optimize, and correct after the fact often backfires. Rather than fostering resilience, it reinforces the very fear circuits that sustain anxiety. This article examines why attempts to be “better” through post‑event rumination maintain threat learning, heighten emotional reactivity, and entrench avoidance patterns, and it outlines evidence‑grounded alternatives that weaken fear associations and promote psychological stability.

What Post‑Event Processing (PEP) Is and Why It Matters

PEP Defined in Cognitive Models

Post‑event processing (PEP) refers to repetitive, detailed review of social interactions after they have ended. In socially anxious individuals, this often involves mentally replaying conversations, perceived mistakes, possible judgments, and imagined negative outcomes. PEP was identified as a maintenance process in cognitive models of social anxiety disorder by seminal theorists such as Clark & Wells (1995) and expanded in related work by Rapee & Heimberg (1997). These models emphasize that socially anxious individuals selectively attend to perceived threats, magnify the likelihood and cost of negative evaluation, and allocate cognitive resources to self‑focused analysis after events conclude.

Why PEP Feels Rational but Isn’t

To the anxious mind, rumination feels purposeful: it seems like a form of problem‑solving or self‑improvement. Yet PEP lacks clear goals, resolution, or corrective feedback grounded in objective evidence. Instead of solving a specific problem, PEP repetitively reactivates the memory of a social event, often with a bias toward negative or threatening interpretation. This pattern aligns with perseverative cognition, a psychological construct describing repetitive negative thinking — worry, rumination, and brooding — that physiologically sustains stress responses long after a stressor ends.

Why the Anxious Brain Seeks Certainty and Control After Social Situations

Threat Learning and the Brain’s Bias

The nervous system evolved to detect and learn from threats. In anxiety disorders, this threat detection system — involving structures such as the amygdala and interconnected networks — becomes sensitized to ambiguity and potential negative evaluation. Rather than reliably updating a non‑threat memory, the anxious brain treats uncertainty as a problem requiring resolution. This drives post‑event analysis as an attempt to pre‑empt future threat, even when none objectively occurred. This dynamic resembles findings from threat conditioning and extinction research, which show that anxiety is associated with difficultly extinguishing learned threat associations once they are encoded.

Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU) — a cognitive bias toward perceiving ambiguous situations as inherently threatening — predicts higher engagement in rumination and other forms of repetitive negative thinking. In social anxiety, higher IU correlates with greater negative appraisal of social experiences, even those devoid of actual threat, because ambiguity itself becomes aversive.

Why Attempts at Self‑Improvement Backfire

Reinforcement of Threat Associations

Attempting to correct or optimize social responses after the fact strengthens threat learning by repeatedly activating fear circuits in the absence of disconfirming evidence. Each cycle of post‑event analysis functions like an implicit “training session” for the brain: it signals that the previous event was significant or dangerous enough to merit review. The result is increased salience of perceived threats and prolonged activation of anxiety networks, rather than habituation or emotional regulation that would occur if the event were allowed to recede without mental elaboration.

Safety Behaviors Maintain Anxiety

Behavioral safety strategies — such as mentally reviewing events to avoid future missteps — paradoxically maintain anxiety. Research on PEP shows that baseline state anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty, and use of safety behaviors predict greater rumination following social stressors. This suggests that attempts at control reinforce the very cycles they aim to prevent.

Distinguishing Productive Learning from Rumination

Productive Learning

- Focuses on a specific question with a bounded goal

- Is time‑limited and evidence‑based

- Occurs in context of clear feedback

Anxiety‑Driven Rumination

- Is repetitive and open‑ended

- Seeks certainty where none is available

- Amplifies perceived threat without grounding in evidence

For example, reviewing whether you achieved a specific social goal (e.g., “Was I able to ask the question I intended?”) is qualitatively different from rehashing every detail with an implicit assumption that something must be wrong.

Introducing No Mental Closure

What It Means

No Mental Closure refers to a counter‑intuitive principle whereby an event remains cognitively unfinished without analysis, resolution, or lesson extraction. Unlike suppression or denial, No Mental Closure acknowledges the memory without attempting to finalize its meaning.

Why It Weakens Threat Learning

Leaving events unresolved means that the brain does not repeatedly activate threat networks in search of a conclusion. In inhibitory learning models — derived from exposure research — repeated experience of non‑threatening stimuli without avoidance strengthens new associations that inhibit fear responses. This leads to decoupling of uncertainty from danger and lowers emotional intensity tied to social memories.

Acceptance of Imperfection

Why Optimization Undermines Resilience

Efforts to be “stronger next time” or to avoid any perceived flaw reflect control‑seeking rather than tolerance of uncertainty. In anxiety disorders, perfectionistic tendencies and attempts at correction increase focus on potential threat cues rather than promoting flexible adaptation. This aligns with findings that intolerance of uncertainty and perfectionism are linked with greater repetitive negative thinking.

What Acceptance Entails

Acceptance of Imperfection involves recognizing that ambiguity and occasional awkwardness are inherent to social interactions. This mindset shifts the cognitive emphasis from performance evaluation to experience integration, reducing the salience of negative self‑focused appraisals and the urgency to “fix” memories that are non‑harmful.

Why This Feels Wrong but Works

Neuroscience and Learning Theory

From a neuroscientific standpoint, the anxious brain expects consistency and predictability; uncertainty triggers heightened arousal and vigilance. Attempts at post‑event analysis temporarily reduce subjective uncertainty but reinforce threat circuitry because they treat ambiguity as if it were dangerous. In contrast, No Mental Closure and acceptance principles align with inhibitory learning: by withholding reinforcement and not reactivating threat memories, the nervous system begins to encode uncertainty as non‑dangerous. Over time this decreases amygdala hyper‑reactivity to ambiguous social cues and supports emotion regulation.

What Not to Do After a Social Event — and What to Do Instead

Avoid

- Extended analysis of conversations or body language

- Searching for implicit judgments you might have received

- Planning “better” responses for the next time

- Rehearsing perceived mistakes

Instead

- Label the urge to analyze as rumination rather than problem‑solving

- Acknowledge the event without assigning meaning

- Redirect cognitive attention to ongoing activities

- Let memories of harmless events fade without added interpretation

These alternatives reflect cognitive learning principles that decrease the salience of perceived threats and support tolerance of uncertainty, rather than reinforcing fear.

Conclusion

In anxiety disorders, the drive to be “better” by analyzing social experiences after they occur often strengthens the very patterns it aims to resolve. Post‑event rumination, fueled by intolerance of uncertainty and safety behaviors, reinforces threat circuits instead of promoting emotional regulation or resilience. Evidence from cognitive and learning theory suggests that leaving events without exhaustive mental closure and accepting imperfection weakens threat learning and retrains the nervous system to tolerate ambiguity. Psychological strength in anxiety is not built by fixing or understanding every experience, but by shifting the cognitive weight away from post‑event optimization toward tolerance of uncertainty and acceptance of non‑harmful imperfection.

References

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive‑behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756.

Shikatani, B., Antony, M. M., Cassin, S. E., & Kuo, J. R. (2016). Examining the role of perfectionism and intolerance of uncertainty in post‑event processing in social anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

National Social Anxiety Center. (2019). Pre‑ and post‑event rumination important factors in social anxiety.

Knowles, K. A., et al. (2018). Enhancing inhibitory learning: The utility of variability in exposure therapy. Frontiers in Psychology.